Autumn 2025

Gathering together

Civil participation

Joyful resistance

A child’s eye view

Exophony, or beyond one’s mother tongue

Playfulness

Copies of all the books included in our summer 15 Reads are available to browse at CAMPLE LINE or to borrow through Dumfries and Galloway Libraries

In A Paradise Built in Hell, Rebecca Solnit asks what societies would feel and look like if joy were given greater precedence, even in adversity, where ‘ethics, ideals, a chance at heroism, at shaping history, a set of motivations based on principles’ were able to flourish?

Compassion, solidarity and creativity in adversity are the touchstones that bring these 15 Reads into conversation with one another, revealing remarkable stories garnered from experience as well as from pure, often playful, inventiveness. Some also express the radical potential of exophony (writing or living beyond one’s mother tongue) and the spaces in between languages and geographies.

As always, these autumn reads express our commitment to independent publishers and celebrating women’s voices, stories from marginalised communities and works in translation.

Rebecca Solnit

A Paradise Built in Hell. The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster

A close reading of personal accounts and analysis of trauma studies ground Solnit’s examination of the impact upon local populations of five disasters.

Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell. The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster, (2009), Granta, 2020

A close reading of personal accounts and analysis of trauma studies ground Solnit’s examination of the impact upon local populations of five disasters: the San Francisco earthquake (1906); the 1917 explosion in Halifax; the Mexico City earthquake (1985); the September 11 attacks (2001); and Hurricane Katrina (2005). Although each resulted in mass loss of life and decimation of place, ordinary people who were directly impacted came together to organise and to care for each other. In each extreme situation, Solnit examines how mutual support within those communities enabled people to find their own solutions rather than become passive recipients of external aid. Such demonstrations of community creativity and resilience brought profound satisfaction and joy, even in the midst of personal loss; these experiences being akin to the celebratory coming together during fiestas and carnivals which Solnit tells us ‘produce society’, for they too ‘renew the reasons why we might want to belong and the feelings we do.’

Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell. The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster, (2009), Granta, 2020

A close reading of personal accounts and analysis of trauma studies ground Solnit’s examination of the impact upon local populations of five disasters: the San Francisco earthquake (1906); the 1917 explosion in Halifax; the Mexico City earthquake (1985); the September 11 attacks (2001); and Hurricane Katrina (2005). Although each resulted in mass loss of life and decimation of place, ordinary people who were directly impacted came together to organise and to care for each other. In each extreme situation, Solnit examines how mutual support within those communities enabled people to find their own solutions rather than become passive recipients of external aid. Such demonstrations of community creativity and resilience brought profound satisfaction and joy, even in the midst of personal loss; these experiences being akin to the celebratory coming together during fiestas and carnivals which Solnit tells us ‘produce society’, for they too ‘renew the reasons why we might want to belong and the feelings we do.’

Raymond Williams Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism

The essays by Raymond Williams (1921-88) collected together posthumously under the title Resources of Hope were first delivered as a lectures or published by Williams over a number of decades from the late 1950s through to the last six months of his life.

Raymond Williams, Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism, edited by Robin Gable, Verso Books, 1989

The essays by Raymond Williams (1921-88) collected together posthumously under the title Resources of Hope were first delivered as a lectures or published over decades, from the late 1950s to the last six months of his life. The volume touches on themes that were central to his thought, including the nature of a democratic culture and the value of community. In collaboration with Joy Williams, Robin Gable has selected important early writings such as ‘Culture is Ordinary’ and ‘Why Do I Demonstrate?’ – the latter published in April 1968 in the context of Williams having joined protests, including against the Vietnam War. The lucidity and humanity of Williams’ writing remain deeply striking and his words feel at times shockingly prescient: ‘Today in a score of countries, the protest march has become a regular part of political activity. In the past in Britain… there was a style of demonstration that pre-dated liberal democracy, the march of men without votes representing that majority who were excluded from political decision, and a march through the streets with banners because this was still the quickest and most visible means of communication. Today the means of communication are much more developed…the theory of representative democracy, with all its strengths and limitations, is being itself surpassed…And a key role in this replacement of representative democracy is being played by the modern communications system, which is not, and does not pretend to be, democratic at all, except in purely negative ways.’

Raymond Williams, Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism, edited by Robin Gable, Verso Books, 1989

The essays by Raymond Williams (1921-88) collected together posthumously under the title Resources of Hope were first delivered as a lectures or published over decades, from the late 1950s to the last six months of his life. The volume touches on themes that were central to his thought, including the nature of a democratic culture and the value of community. In collaboration with Joy Williams, Robin Gable has selected important early writings such as ‘Culture is Ordinary’ and ‘Why Do I Demonstrate?’ – the latter published in April 1968 in the context of Williams having joined protests, including against the Vietnam War. The lucidity and humanity of Williams’ writing remain deeply striking and his words feel at times shockingly prescient: ‘Today in a score of countries, the protest march has become a regular part of political activity. In the past in Britain… there was a style of demonstration that pre-dated liberal democracy, the march of men without votes representing that majority who were excluded from political decision, and a march through the streets with banners because this was still the quickest and most visible means of communication. Today the means of communication are much more developed…the theory of representative democracy, with all its strengths and limitations, is being itself surpassed…And a key role in this replacement of representative democracy is being played by the modern communications system, which is not, and does not pretend to be, democratic at all, except in purely negative ways.’

Hwang Sok-yong

Mater 2-10

Inspired by a conversation with an elderly man during an illicit visit that Hwang Sok-yong made to North Korea, this novel was thirty years in the making. Spanning the great political and social upheavals of the twentieth century and the impact of late capitalism, this is the story of four generations of a family of manual labourers.

Hwang Sok-yong, Mater 2-10, (2020), translated by Sora Kim-Russell and Youngjae Josephine Bae, Scribe Publications, 2024

Inspired by a conversation with an elderly man during an illicit visit that Hwang Sok-yong made to North Korea, this novel was thirty years in the making. Spanning the great political and social upheavals of the twentieth century and the impact of late capitalism, this is the story of four generations of a family of manual labourers. Their lives are relayed to Yi Jino in dream-like sequences as he camps out high up on a factory chimney catwalk.

Supported by his fellow trade unionists who are on the ground, Jino is protesting the factory buy-out and the resulting lay-off of workers. In doing so, he continues the tradition of his forebears who participated in communal labour activism both for ideological reasons and for survival, each in their own way fighting against political, social and economic oppression. Their story, Hwang Sok-yong writes, is the story of Korea’s industrial workers whose voices until now have remained untold in Korean literature, yet whose communal struggles still shape the lives of those living in the Korean peninsula.

Hwang Sok-yong, Mater 2-10, (2020), translated by Sora Kim-Russell and Youngjae Josephine Bae, Scribe Publications, 2024

Inspired by a conversation with an elderly man during an illicit visit that Hwang Sok-yong made to North Korea, this novel was thirty years in the making. Spanning the great political and social upheavals of the twentieth century and the impact of late capitalism, this is the story of four generations of a family of manual labourers. Their lives are relayed to Yi Jino in dream-like sequences as he camps out high up on a factory chimney catwalk.

Supported by his fellow trade unionists who are on the ground, Jino is protesting the factory buy-out and the resulting lay-off of workers. In doing so, he continues the tradition of his forebears who participated in communal labour activism both for ideological reasons and for survival, each in their own way fighting against political, social and economic oppression. Their story, Hwang Sok-yong writes, is the story of Korea’s industrial workers whose voices until now have remained untold in Korean literature, yet whose communal struggles still shape the lives of those living in the Korean peninsula.

Azar Nafisi

Reading Lolita in Tehran. A Memoir in Books

Returning from America to Iran in 1979, Azar Nafisi recalls surviving years of revolution, war and purges during which she attempted to maintain intellectual and personal freedom as a woman and an academic in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran. A Memoir in Books, (2003), Penguin Modern Classics, 2015

Returning from America to Iran in 1979, Azar Nafisi recalls surviving years of revolution, war and purges during which she attempted to maintain intellectual and personal freedom as a woman and an academic within the Islamic Republic of Iran. Unable to continue teaching at the university in Tehran, Nafisi brings together a clandestine group of female students who visit her home to study literature banned by the state. Through their close readings of Nabokov, Austen and James, each of the women express their experiences surviving within the totalitarian state. Through their shared intimacy, each reveals aspects of their lives and ultimately their desire for the freedom to imagine and to shape their futures.

Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran. A Memoir in Books, (2003), Penguin Modern Classics, 2015

Returning from America to Iran in 1979, Azar Nafisi recalls surviving years of revolution, war and purges during which she attempted to maintain intellectual and personal freedom as a woman and an academic within the Islamic Republic of Iran. Unable to continue teaching at the university in Tehran, Nafisi brings together a clandestine group of female students who visit her home to study literature banned by the state. Through their close readings of Nabokov, Austen and James, each of the women express their experiences surviving within the totalitarian state. Through their shared intimacy, each reveals aspects of their lives and ultimately their desire for the freedom to imagine and to shape their futures.

Yoko Tawada

Exophony: Voyages Outside the Mother Tongue

Each essay in this volume is located in a different city but together they explore the radical potential of exophony, that is, to write or live beyond one’s mother tongue.

Yoko Tawada, Exophony: Voyages Outside the Mother Tongue, (2003), translated by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, introduced by Naoise Dolan, Dialogue Books, 2025

Each essay in this volume is located in a different city but together they explore the radical potential of exophony, that is, to write or live beyond one’s mother tongue. A native Japanese speaker who adopted the German language, Yoko Tawada explores the creative freedom that can arise from writing in or outside of those languages, or in-between, opening up new possibilities for playful intellectual and linguistic adventure. ‘It’s the space between languages that most interests me’, Tawada tells us, ‘maybe what I really want is not to be a writer of this or that language in particular, but to fall into the poetic ravine between them’. In this way, as an exophonic writer, Tawada experiences a release from nostalgia for homeland and for her mother tongue; her writing is able to exceed state borders, critique colonially imposed language and disrupt the dominance of English. It is a means to perhaps ‘create new communities wherever we live’.

Yoko Tawada, Exophony: Voyages Outside the Mother Tongue, (2003), translated by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, introduced by Naoise Dolan, Dialogue Books, 2025

Each essay in this volume is located in a different city but together they explore the radical potential of exophony, that is, to write or live beyond one’s mother tongue. A native Japanese speaker who adopted the German language, Yoko Tawada explores the creative freedom that can arise from writing in or outside of those languages, or in-between, opening up new possibilities for playful intellectual and linguistic adventure. ‘It’s the space between languages that most interests me’, Tawada tells us, ‘maybe what I really want is not to be a writer of this or that language in particular, but to fall into the poetic ravine between them’. In this way, as an exophonic writer, Tawada experiences a release from nostalgia for homeland and for her mother tongue; her writing is able to exceed state borders, critique colonially imposed language and disrupt the dominance of English. It is a means to perhaps ‘create new communities wherever we live’.

Mimi Khalvati

In White Ink

Snippets, glimpses, memories. Family, strangers, places. Womanhood, motherhood, daughterhood, childhood. Fleeting moments, half recalled in English are interjected with Farsi words and phrases recovered from Mimi Khalvati’s early childhood.

Mimi Khalvati, In White Ink, Carcanet Press, 1991

Snippets, glimpses, memories. Family, strangers, places. Womanhood, motherhood, daughterhood, childhood. Fleeting moments, half recalled in English are interjected with Farsi words and phrases recovered from Mimi Khalvati’s early childhood before she was sent from Iran to an English boarding school aged just six. Separated from her culture and her mother tongue, at times language necessarily becomes one of gestures, such as reading meaning into the fall of rose petals from the hands of her Iranian-speaking grandmother. Mixing traditional and free verse, Khalvati’s intimate, often conversational poems are vivid with flowers and creatures which reflect her inner world and her position as a woman and a mother in her adopted land.

Mimi Khalvati, In White Ink, Carcanet Press, 1991

Snippets, glimpses, memories. Family, strangers, places. Womanhood, motherhood, daughterhood, childhood. Fleeting moments, half recalled in English are interjected with Farsi words and phrases recovered from Mimi Khalvati’s early childhood before she was sent from Iran to an English boarding school aged just six. Separated from her culture and her mother tongue, at times language necessarily becomes one of gestures, such as reading meaning into the fall of rose petals from the hands of her Iranian-speaking grandmother. Mixing traditional and free verse, Khalvati’s intimate, often conversational poems are vivid with flowers and creatures which reflect her inner world and her position as a woman and a mother in her adopted land.

For younger readers: José Mauro de Vasconcelos

My Sweet Orange Tree

Growing up in poverty, five-year-old Zezé seeks refuge from life’s harsh realities by playing pranks or by retreating into his imagination. A wizard at marbles, he stars as a cowboy in his own games, has an eye to making a few tostão (coins) and doesn’t miss the chance to steal a ripe guava

For younger readers: José Mauro de Vasconcelos, My Sweet Orange Tree, (1968), translated by Alison Entrekin, Pushkin Press, 2018

Growing up in poverty, five-year-old Zezé seeks refuge from life’s harsh realities by playing pranks or by retreating into his imagination. A wizard at marbles, he stars as a cowboy in his own games, has an eye to making a few tostão (coins) and doesn’t miss the chance to steal a ripe guava. Zezé’s sole confidant is Sweetie, the sweet orange tree which grows in the family’s garden, until he meets Portuga, who brings tenderness and understanding into the little boy’s life. A Brazilian children’s classic, based on the author’s childhood, this is an episodic story giving a child’s eye view of the world, expressing the powerlessness Zezé often feels not only as the scapegoat of the family but in an adult world that seems incomprehensible.

For younger readers: José Mauro de Vasconcelos, My Sweet Orange Tree, (1968), translated by Alison Entrekin, Pushkin Press, 2018

Growing up in poverty, five-year-old Zezé seeks refuge from life’s harsh realities by playing pranks or by retreating into his imagination. A wizard at marbles, he stars as a cowboy in his own games, has an eye to making a few tostão (coins) and doesn’t miss the chance to steal a ripe guava. Zezé’s sole confidant is Sweetie, the sweet orange tree which grows in the family’s garden, until he meets Portuga, who brings tenderness and understanding into the little boy’s life. A Brazilian children’s classic, based on the author’s childhood, this is an episodic story giving a child’s eye view of the world, expressing the powerlessness Zezé often feels not only as the scapegoat of the family but in an adult world that seems incomprehensible.

Liliana Heker

Please Talk to Me: Selected Stories

Throughout Argentina’s military dictatorships, rather than seeking exile, Liliana Heker chose to continue to write and to publish, taking an active part in what she described as ‘cultural resistance’, carving out a small space of freedom in her writing.

Liliana Heker, Please Talk to Me: Selected Stories, edited and with an introduction by Alberton Manguel, translated by Alberto Manguel and Miranda France, Margellos, World Republic of Letters, Yale University Press, 2015.

Throughout Argentina’s military dictatorships, rather than seeking exile, Liliana Heker chose to continue to write and to publish, taking an active part in what she described as ‘cultural resistance’, carving out a small space of freedom in her writing. The resulting short stories explore notions of fantasy versus painful reality, hidden truths and liberation through imagination. With their focus on family and the impact of the wider world upon her characters, events are often seen from a child’s perspective, each story a distillation of experience, with each amounting to more than the sum of their parts.

Liliana Heker, Please Talk to Me: Selected Stories, edited and with an introduction by Alberton Manguel, translated by Alberto Manguel and Miranda France, Margellos, World Republic of Letters, Yale University Press, 2015.

Throughout Argentina’s military dictatorships, rather than seeking exile, Liliana Heker chose to continue to write and to publish, taking an active part in what she described as ‘cultural resistance’, carving out a small space of freedom in her writing. The resulting short stories explore notions of fantasy versus painful reality, hidden truths and liberation through imagination. With their focus on family and the impact of the wider world upon her characters, events are often seen from a child’s perspective, each story a distillation of experience, with each amounting to more than the sum of their parts.

Madeleine Thien

The Book of Records

This multifarious story is founded upon Spinoza’s Ethics, published in 1677. Episodes from Spinoza’ life are collaged with moments in the lives of philosopher Hannah Arendt and the Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu, who, like the imaginary characters in the book, are shown in moments of crisis

Madeleine Thien, The Book of Records, Granta, 2025

This multifarious story is founded upon Spinoza’s Ethics (1677). Episodes from Spinoza’s life are collaged with moments in the lives of philosopher Hannah Arendt and the Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu, who, like the imaginary characters in the book, are shown in moments of crisis. Recalling events from nearly fifty years ago, when as a child she and her father arrive at The Sea, home to thousands in migratory transit, Lina recounts stories about Spinoza, Arendt and Du Fu as told by her neighbours. Accompanied by Brother Orange the cat who moves freely between each character’s different worlds, Lina experiences other histories of exile and family crisis as well humanity’s capacity for joy in the darkest of times, as the events which separated Lina from her mother and her brother are revealed.

Madeleine Thien, The Book of Records, Granta, 2025

This multifarious story is founded upon Spinoza’s Ethics (1677). Episodes from Spinoza’s life are collaged with moments in the lives of philosopher Hannah Arendt and the Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu, who, like the imaginary characters in the book, are shown in moments of crisis. Recalling events from nearly fifty years ago, when as a child she and her father arrive at The Sea, home to thousands in migratory transit, Lina recounts stories about Spinoza, Arendt and Du Fu as told by her neighbours. Accompanied by Brother Orange the cat who moves freely between each character’s different worlds, Lina experiences other histories of exile and family crisis as well humanity’s capacity for joy in the darkest of times, as the events which separated Lina from her mother and her brother are revealed.

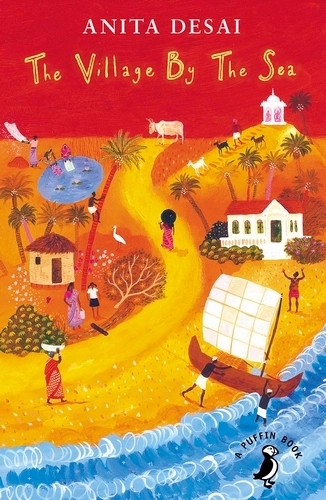

For younger readers: Anita Desai

The Village by the Sea

The idyllic setting of the village of Thul, with its coconut groves and glittering sea, belies the poverty which Lila and her brother Hari struggle against.

Anita Desai, The Village by the Sea, (1982) Puffin Books, 2015

The idyllic setting of the village of Thul, with its coconut groves and glittering sea, belies the poverty which Lila and her brother Hari struggle against. With a sick mother, a toddy-drinking father and younger siblings to rear, daily life is difficult enough without the impending factory development, which threatens to destroy the area’s subsistence fishing and farming. Seeing no way to secure his family’s future by remaining in Thul, Hari joins a group of farmers and fishermen who make their way to Bombay to protest against the factory. Separated from the group and friendless in the big city, it is only through the goodwill of strangers that Hari not only survives but formulates a plan to ensure his family’s future. Lyrical and ultimately heartwarming this is a story about fortitude, family and kindness.

Anita Desai, The Village by the Sea, (1982) Puffin Books, 2015

The idyllic setting of the village of Thul, with its coconut groves and glittering sea, belies the poverty which Lila and her brother Hari struggle against. With a sick mother, a toddy-drinking father and younger siblings to rear, daily life is difficult enough without the impending factory development, which threatens to destroy the area’s subsistence fishing and farming. Seeing no way to secure his family’s future by remaining in Thul, Hari joins a group of farmers and fishermen who make their way to Bombay to protest against the factory. Separated from the group and friendless in the big city, it is only through the goodwill of strangers that Hari not only survives but formulates a plan to ensure his family’s future. Lyrical and ultimately heartwarming this is a story about fortitude, family and kindness.

Anna Chapman Parker

Understorey, A Year Among Weeds

Written following the progression of a year from January through to December, Understorey is a meditation on observation through the practice of drawing.

Anna Chapman Parker, Understorey, A Year Among Weeds, Duckworth, 2024

Written following the progression of a year from January through to December, Understorey is a meditation on observation through the practice of drawing. Grabbing moments of time to stop, notice, note and draw (in amongst the demands of motherhood), the small wild plants thriving in the cracks of pavements, around the edges of carparks and roadside verges in the north of England where Chapman Parker lives become the focus of a process of registering and committing to paper. But rather than being a record of looking and recording facts, Chapman Parker’s drawings (which are interspersed throughout) are much more a record of being there, of a sustained attention often at odds with how we live and move through our surroundings. ‘I want to feel immersed in the particular, in the detail, right among it: my heels digging into the soil, my elbow brushing the long grass’. What she comes to know- in that particular moment, in that particular place – she arrives at through direct observation and through drawing: ‘the drawn line a means of fastening your attention to what’s there.’ If drawing fails to preserve the plants themselves, it does preserve that failure, that effort, those moments and that connection.

Anna Chapman Parker, Understorey, A Year Among Weeds, Duckworth, 2024

Written following the progression of a year from January through to December, Understorey is a meditation on observation through the practice of drawing. Grabbing moments of time to stop, notice, note and draw (in amongst the demands of motherhood), the small wild plants thriving in the cracks of pavements, around the edges of carparks and roadside verges in the north of England where Chapman Parker lives become the focus of a process of registering and committing to paper. But rather than being a record of looking and recording facts, Chapman Parker’s drawings (which are interspersed throughout) are much more a record of being there, of a sustained attention often at odds with how we live and move through our surroundings. ‘I want to feel immersed in the particular, in the detail, right among it: my heels digging into the soil, my elbow brushing the long grass’. What she comes to know- in that particular moment, in that particular place – she arrives at through direct observation and through drawing: ‘the drawn line a means of fastening your attention to what’s there.’ If drawing fails to preserve the plants themselves, it does preserve that failure, that effort, those moments and that connection.

Jeremy Cooper

Brian

Risk averse loner Brian lives a quiet, ordered life, working for the Council and watching tv in the evenings, until a visit to the British Film Institute heralds a slow, gentle change.

Jeremy Cooper, Brian, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2024

Risk averse loner Brian lives a quiet, ordered life, working for the Council and watching tv in the evenings, until a visit to the British Film Institute heralds a slow, gentle change. Being nothing but methodical, Brian incorporates nightly screenings at London’s Southbank into his evening routine and soon becomes accepted as a regular into a community of film buffs. His special interest in post-war Japanese cinema and his obsessive knowledge of the more obscure films within this genre provide him not only with a nightly escape from life’s vagaries but also the possibility of friendship. This is a gentle story, as much a paeon to cinema, as to the opportunities which art offers to shape our experiences and connections with the world.

Jeremy Cooper, Brian, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2024

Risk averse loner Brian lives a quiet, ordered life, working for the Council and watching tv in the evenings, until a visit to the British Film Institute heralds a slow, gentle change. Being nothing but methodical, Brian incorporates nightly screenings at London’s Southbank into his evening routine and soon becomes accepted as a regular into a community of film buffs. His special interest in post-war Japanese cinema and his obsessive knowledge of the more obscure films within this genre provide him not only with a nightly escape from life’s vagaries but also the possibility of friendship. This is a gentle story, as much a paeon to cinema, as to the opportunities which art offers to shape our experiences and connections with the world.

Edgardo Cozarinsky

Milongas

Embedded in carnival and dance hall culture, Edgardo Cozarinsky maps histories of milonga and its close associate tango. In brief snatches, like the beguiling music itself heard through an open window, he records milonga’s gaucho origins and its place in Buenos Aires’ ‘clandestine’ working class culture.

Edgardo Cozarinsky, Milongas, (2007), with a preface by Alberto Manguel, translated by Valerie Miles, Archipelago Books, 2021

Embedded in carnival and dance hall culture, Edgardo Cozarinsky maps histories of milonga and its close associate tango. In brief snatches, like the beguiling music itself heard through an open window, he records milonga’s gaucho origins and its place in Buenos Aires’ ‘clandestine’ working class culture. He traces its shift to polite Parisian salons and New York Theatres at the turn of the twentieth century, also recording milonga’s wider global reach from Poland to Tokyo, Egypt to Moscow. Described by Alberto Manguel in the Preface as Cozarinsky’s ‘autobiographical confession’ — Cozarinsky was a practitioner as well as an historian of the artform — his is an anecdotal account of the music, the dance and the groups who embraced it. Widely celebrated, notably in Jorge Luis Borges’ famous poem el tango, Cozarinsky describes how across cultures and time, in the times of war, revolution and carnival, milonga ‘allows one to live a fiction, to act out as characters in a fleeting novel, that nevertheless expresses something that is true, that is no less authentic for being imaginary’.

Edgardo Cozarinsky, Milongas, (2007), with a preface by Alberto Manguel, translated by Valerie Miles, Archipelago Books, 2021

Embedded in carnival and dance hall culture, Edgardo Cozarinsky maps histories of milonga and its close associate tango. In brief snatches, like the beguiling music itself heard through an open window, he records milonga’s gaucho origins and its place in Buenos Aires’ ‘clandestine’ working class culture. He traces its shift to polite Parisian salons and New York Theatres at the turn of the twentieth century, also recording milonga’s wider global reach from Poland to Tokyo, Egypt to Moscow. Described by Alberto Manguel in the Preface as Cozarinsky’s ‘autobiographical confession’ — Cozarinsky was a practitioner as well as an historian of the artform — his is an anecdotal account of the music, the dance and the groups who embraced it. Widely celebrated, notably in Jorge Luis Borges’ famous poem el tango, Cozarinsky describes how across cultures and time, in the times of war, revolution and carnival, milonga ‘allows one to live a fiction, to act out as characters in a fleeting novel, that nevertheless expresses something that is true, that is no less authentic for being imaginary’.

Karen King-Aribisala

Kicking Tongues

Forty strangers come together under the leadership of the formidable ‘The Black Lady The’ in this Canterbury Tales–inspired satire set in Nigeria at the end of the twentieth century.

Karen King-Aribisala, Kicking Tongues, Black Star Books and Head of Zeus, Bloomsbury Publishing,1998

Forty strangers come together under the leadership of the formidable ‘The Black Lady The’ in this Canterbury Tales-inspired satire set in Nigeria at the end of the twentieth century. Together, theirs is a journey of protest against deceit, killings and corruption, and at the same of atonement inspired by ‘a yearning/For/Some other life’. As the travellers make their way by bus from Lagos to the new capital Abuja, The Black Lady The recounts their wildly different stories: the dentist who speaks of the decay at the heart of government; the corrupt lady police officer; the maid whose life reveals the injustices and double standards of the newly wealthy; the rain maker; the boutique owner who no longer sells dresses but deals in queues in order to adhere to the new nationalism; and the Chief. Of course, she tells her own story too as The Black Lady The, named so due to the mourning she wears.

Karen King-Aribisala, Kicking Tongues, Black Star Books and Head of Zeus, Bloomsbury Publishing,1998

Forty strangers come together under the leadership of the formidable ‘The Black Lady The’ in this Canterbury Tales-inspired satire set in Nigeria at the end of the twentieth century. Together, theirs is a journey of protest against deceit, killings and corruption, and at the same of atonement inspired by ‘a yearning/For/Some other life’. As the travellers make their way by bus from Lagos to the new capital Abuja, The Black Lady The recounts their wildly different stories: the dentist who speaks of the decay at the heart of government; the corrupt lady police officer; the maid whose life reveals the injustices and double standards of the newly wealthy; the rain maker; the boutique owner who no longer sells dresses but deals in queues in order to adhere to the new nationalism; and the Chief. Of course, she tells her own story too as The Black Lady The, named so due to the mourning she wears.

Solvej Balle

On the Calculation of Volume

Here is a character in existential crisis, who somehow slipped out of progressive time, awakening each day to the same 18 November, reliving the same weather patterns, the same bird song, the same activities her husband undertakes

Solvej Balle, On the Calculation of Volume, Book 1, (2020), translated by Barbara J. Haveland, Faber, 2024.

Here is a character in existential crisis, who somehow slipped out of progressive time, awakening each day to the same 18th November, reliving the same weather patterns, the same bird song, the same activities her husband undertakes. But she is the only one who recognises these diurnal repetitions, and she is the only one able to create variety in the day. At first this brings freedom as nothing matters for there are no consequences, but as the same day continues to replicate, Tara becomes increasingly isolated. As she searches for a means to restore time’s flow, Tara records each variation in her otherwise monotonous day: the burn on her hand healing, objects remaining where she leaves them, planets continuing to orbit the sun.

Solvej Balle, On the Calculation of Volume, Book 1, (2020), translated by Barbara J. Haveland, Faber, 2024.

Here is a character in existential crisis, who somehow slipped out of progressive time, awakening each day to the same 18th November, reliving the same weather patterns, the same bird song, the same activities her husband undertakes. But she is the only one who recognises these diurnal repetitions, and she is the only one able to create variety in the day. At first this brings freedom as nothing matters for there are no consequences, but as the same day continues to replicate, Tara becomes increasingly isolated. As she searches for a means to restore time’s flow, Tara records each variation in her otherwise monotonous day: the burn on her hand healing, objects remaining where she leaves them, planets continuing to orbit the sun.