15 READS - spring 24

Interior/exterior worlds

Memory

Cityscapes

Ruptures and severances

Click here to download this list (Word version).

Each edition is selected and described by Dr Jane McArthur, a writer and arts producer based in Dumfries and Galloway

Clemens Meyer

Dark Satellites

Beguiling in their easy literary style, this short story collection expresses the fragility of life on the periphery.

Clemens Meyer, Dark Satellites, (2017), trans. Katy Derbyshire, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020.

The city, a fractured place of transitory connections where history persists in the Ex-GDR housing estates, in semi derelict buildings, along the train tracks and beside motorways. These are places where memories resurface in moments of crisis, where past and present are fluid, where chance encounters or random actions expose cracks in the lives of Meyer’s characters. Beguiling in their easy literary style, this short story collection expresses the fragility of life on the periphery experienced by the security guard, the cleaner, the train driver, the refugee, the railway planner, the man who calls his wife just to hear her voice on the answer phone, or the German revolutionary who wants to believe in a new world as he writes a novel in the Lenin Library while the bombs fall.

Clemens Meyer, Dark Satellites, (2017), trans. Katy Derbyshire, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020.

The city, a fractured place of transitory connections where history persists in the Ex-GDR housing estates, in semi derelict buildings, along the train tracks and beside motorways. These are places where memories resurface in moments of crisis, where past and present are fluid, where chance encounters or random actions expose cracks in the lives of Meyer’s characters. Beguiling in their easy literary style, this short story collection expresses the fragility of life on the periphery experienced by the security guard, the cleaner, the train driver, the refugee, the railway planner, the man who calls his wife just to hear her voice on the answer phone, or the German revolutionary who wants to believe in a new world as he writes a novel in the Lenin Library while the bombs fall.

Ian Sinclair

Lights Out for the Territory

Drawing connections between local characters and events, artists, filmmakers and writers, Sinclair uncovers the rhizomatic connections underpinning life in the capital which is being subsumed by redevelopment.

Ian Sinclair, Lights Out for the Territory, (1997), Penguin, 2003.

Navigating between London’s overlooked, neglected areas and its sites of financial and political power, Sinclair draws complex cityscapes from billboards, cemeteries, and penthouse views, shop signs, graffiti, churches, and booksellers. His anarchic perspective is that of the urban wanderer who, like the Situationists before him, exposes cultures within everyday life and unravels the micro histories of place. Drawing connections between local characters and events, artists, filmmakers and writers, he uncovers the rhizomatic connections underpinning life in the capital which is being subsumed by redevelopment.

Ian Sinclair, Lights Out for the Territory, (1997), Penguin, 2003.

Navigating between London’s overlooked, neglected areas and its sites of financial and political power, Sinclair draws complex cityscapes from billboards, cemeteries, and penthouse views, shop signs, graffiti, churches, and booksellers. His anarchic perspective is that of the urban wanderer who, like the Situationists before him, exposes cultures within everyday life and unravels the micro histories of place. Drawing connections between local characters and events, artists, filmmakers and writers, he uncovers the rhizomatic connections underpinning life in the capital which is being subsumed by redevelopment.

Orhan Pamuk,

Istanbul: Memories and the City

Interwoven with recollections of Pamuk’s childhood and adolescence are the cityscapes recorded by nineteenth century artists, photographers and writers who visited Istanbul in search of a pre-supposed orientalism, but who found instead, dilapidated streets redolent with an end of Empire melancholy.

Orhan Pamuk, Istanbul: Memories and the City, (2003), trans. Maureen Freely, Faber, 2017.

Interwoven with recollections of Pamuk’s childhood and adolescence are the cityscapes recorded by nineteenth century artists, photographers and writers who visited Istanbul in search of a pre-supposed orientalism, but who found instead, dilapidated streets redolent with an end of Empire melancholy. Pamuk identifies this same atmosphere lingering in the crumbling mansions still lining the Bosphorus and in the character of its inhabitants. He also recognises this trait in himself, embracing it along with the city that has shaped him, and which provides the context and subjects for his novels.

Orhan Pamuk, Istanbul: Memories and the City, (2003), trans. Maureen Freely, Faber, 2017.

Interwoven with recollections of Pamuk’s childhood and adolescence are the cityscapes recorded by nineteenth century artists, photographers and writers who visited Istanbul in search of a pre-supposed orientalism, but who found instead, dilapidated streets redolent with an end of Empire melancholy. Pamuk identifies this same atmosphere lingering in the crumbling mansions still lining the Bosphorus and in the character of its inhabitants. He also recognises this trait in himself, embracing it along with the city that has shaped him, and which provides the context and subjects for his novels.

Katja Oskamp,

Marzan Mon Amour

Katja Oskamp’s novella follows an unnamed woman, an erstwhile writer now retrained as a chiropodist, and her colleagues Tiffy and Flocke, as they welcome local inhabitants to their treatment rooms in the Marzahn estate in Berlin.

Katja Oskamp, Marzan Mon Amour, (2019), trans. Jo Heinrich, Peirene Press, 2022.

‘I take her little left foot and steadily stroke from the base joints of her toes along her instep towards her ankle joints. Everything feels so delicate, so easily broken. I draw on what I’ve heard over the course of many massages: …One hand must always remain on the foot to avoid the sensation of abandonment.’ Katja Oskamp’s novella follows an unnamed woman, an erstwhile writer now retrained as a chiropodist, and her colleagues Tiffy and Flocke, as they welcome local inhabitants to their treatment rooms in the Marzahn estate in Berlin. Over fifteen short vignettes, she details her encounters with particular clients – Frau Gruse, Herr Paulke, the Russian Woman, Fritz – sharing insights into their ailments, personal histories, characters and relationships with humour and warmth. The treatment room becomes a lens for vulnerabilities — bodily, emotional and social — that are met with small gestures of care and attention.

Katja Oskamp, Marzan Mon Amour, (2019), trans. Jo Heinrich, Peirene Press, 2022.

‘I take her little left foot and steadily stroke from the base joints of her toes along her instep towards her ankle joints. Everything feels so delicate, so easily broken. I draw on what I’ve heard over the course of many massages: …One hand must always remain on the foot to avoid the sensation of abandonment.’ Katja Oskamp’s novella follows an unnamed woman, an erstwhile writer now retrained as a chiropodist, and her colleagues Tiffy and Flocke, as they welcome local inhabitants to their treatment rooms in the Marzahn estate in Berlin. Over fifteen short vignettes, she details her encounters with particular clients – Frau Gruse, Herr Paulke, the Russian Woman, Fritz – sharing insights into their ailments, personal histories, characters and relationships with humour and warmth. The treatment room becomes a lens for vulnerabilities — bodily, emotional and social — that are met with small gestures of care and attention.

Manuel Rivas,

The Last Days of Terra Nova

As a young boy suffering from polio Vincenzo observed the world from inside an iron lung. Now an old man and preparing to be evicted from the building which houses his bookshop, he spends a last night there reflecting on the past.

Manuel Rivas, The Last Days of Terra Nova, (2015), trans. Jacob Rogers, Archipelago Books, 2022.

As a young boy suffering from polio Vincenzo observed the world from inside an iron lung. Now an old man and preparing to be evicted from the building which houses his bookshop, he spends a last night there reflecting on the past. Jumping between remembered events, Vincenzo weaves his life story, which is as complex and alluring as any novel on his bookshelves and is filled with as many extraordinary characters and surreal situations as any author could concoct. Describing his dislocated, subversive, and transient life, he recalls the time of Franco’s dictatorship, democratisation, Basque separatism, and the role the bookshop played in these histories and in the wider Hispanic diaspora.

Manuel Rivas, The Last Days of Terra Nova, (2015), trans. Jacob Rogers, Archipelago Books, 2022.

As a young boy suffering from polio Vincenzo observed the world from inside an iron lung. Now an old man and preparing to be evicted from the building which houses his bookshop, he spends a last night there reflecting on the past. Jumping between remembered events, Vincenzo weaves his life story, which is as complex and alluring as any novel on his bookshelves and is filled with as many extraordinary characters and surreal situations as any author could concoct. Describing his dislocated, subversive, and transient life, he recalls the time of Franco’s dictatorship, democratisation, Basque separatism, and the role the bookshop played in these histories and in the wider Hispanic diaspora.

Tony Judt,

The Memory Chalet

Diagnosed with ALS, an incurable degenerative disorder which rendered him immobile and no longer able to write, Judt recreated a Swiss chalet in his mind’s eye.

Tony Judt, The Memory Chalet, Vintage, 2011.

Diagnosed with ALS, an incurable degenerative disorder which rendered him immobile and no longer able to write, Judt recreated a Swiss chalet in his mind’s eye. Using this place of childhood holidays as a pneumonic device in which to anchor his nightly memories, he recollected and dictated the following day what he termed ‘little histories’. As wise, profound, and perspicacious as his academic writing on post-war Europe, the resulting personal essays chart the immense changes he witnessed growing up in post war Britain and during the early years of his academic life in America.

Tony Judt, The Memory Chalet, Vintage, 2011.

Diagnosed with ALS, an incurable degenerative disorder which rendered him immobile and no longer able to write, Judt recreated a Swiss chalet in his mind’s eye. Using this place of childhood holidays as a pneumonic device in which to anchor his nightly memories, he recollected and dictated the following day what he termed ‘little histories’. As wise, profound, and perspicacious as his academic writing on post-war Europe, the resulting personal essays chart the immense changes he witnessed growing up in post war Britain and during the early years of his academic life in America.

Noreen Masud

A Flat Place

Grounded by her reflections on the still-hidden damage done to peoples from former colonies, Masud undertakes explorative walks in the Cambridgeshire Fens, at Orford Ness, Morecombe Bay and Town Moor in Newcastle, seeking signs of the historical trauma that occurred there.

Noreen Masud, A Flat Place, Hamish Hamilton, 2023.

‘We cannot live in this world without damage or being damaged’, Masud comes to understand during her journeys through Britain’s flat places, as she learns to live with the physical and mental fallout resulting from her traumatising childhood in Lahore. Grounded by her reflections on the still-hidden damage done to peoples from former colonies, she undertakes explorative walks in the Cambridgeshire Fens, at Orford Ness, Morecombe Bay and Town Moor in Newcastle, seeking signs of the historical trauma that occurred there. This research offers a strange comfort, for these places in part embody Masud’s own loss of memory and disassociation, demanding nothing, hiding nothing, and as such, she tells us, eventually providing ‘an ethics to live by’.

Noreen Masud, A Flat Place, Hamish Hamilton, 2023.

‘We cannot live in this world without damage or being damaged’, Masud comes to understand during her journeys through Britain’s flat places, as she learns to live with the physical and mental fallout resulting from her traumatising childhood in Lahore. Grounded by her reflections on the still-hidden damage done to peoples from former colonies, she undertakes explorative walks in the Cambridgeshire Fens, at Orford Ness, Morecombe Bay and Town Moor in Newcastle, seeking signs of the historical trauma that occurred there. This research offers a strange comfort, for these places in part embody Masud’s own loss of memory and disassociation, demanding nothing, hiding nothing, and as such, she tells us, eventually providing ‘an ethics to live by’.

Angus Carlyle

A Downland Index

100 stories recall 100 slow runs made by the author over the course of a year, over the ridges, slopes and clefts of East and West Sussex.

Angus Carlyle, A Downland Index, Uniform Books, 2016.

100 stories recall 100 slow runs made by the author over the course of a year, over the ridges, slopes and clefts of East and West Sussex. Highly attuned to both body and surroundings (spit, sweat, saliva are among the references in the preceding index), this heightened awareness entwines with poetic descriptions of observations remembered; the body breathes throughout. In their fragmentary form, there is a particular pace to the words that arises from shifts such as posture, ‘eyes front’ and ‘eyes down’ while running. What is passed by is observed with all the awkwardness of the body as it travels through, seeking breath and footing in an ever-shifting landscape.

Angus Carlyle, A Downland Index, Uniform Books, 2016.

100 stories recall 100 slow runs made by the author over the course of a year, over the ridges, slopes and clefts of East and West Sussex. Highly attuned to both body and surroundings (spit, sweat, saliva are among the references in the preceding index), this heightened awareness entwines with poetic descriptions of observations remembered; the body breathes throughout. In their fragmentary form, there is a particular pace to the words that arises from shifts such as posture, ‘eyes front’ and ‘eyes down’ while running. What is passed by is observed with all the awkwardness of the body as it travels through, seeking breath and footing in an ever-shifting landscape.

FOR TEENAGE READERS:

RUMER GODDEN

THE RIVER

A place for play, celebration, daydreaming and childhood adventure, the flower-filled garden also harbours danger which suddenly and irrevocably strikes, fracturing the gentle pace of colonial life in the house by the river Ganges.

Rumer Godden, The River, (1946), Virago, 2015.

A place for play, celebration, daydreaming and childhood adventure, the flower-filled garden also harbours danger which suddenly and irrevocably strikes, fracturing the gentle pace of colonial life in the house by the river Ganges. The events which encircle the tragedy are recounted by Harriet who on the cusp of adolescence is trying to navigate her place in family life and come to terms with the part she inadvertently played in the family’s disaster. Together with Rumer Godden, Jean Renoir adapted the novel for his first technicolour film.

Rumer Godden, The River, (1946), Virago, 2015.

A place for play, celebration, daydreaming and childhood adventure, the flower-filled garden also harbours danger which suddenly and irrevocably strikes, fracturing the gentle pace of colonial life in the house by the river Ganges. The events which encircle the tragedy are recounted by Harriet who on the cusp of adolescence is trying to navigate her place in family life and come to terms with the part she inadvertently played in the family’s disaster. Together with Rumer Godden, Jean Renoir adapted the novel for his first technicolour film.

Nathalie Sarautte Tropisms

Remote but charged with intensity, Sarautte’s short stories offer glimpses beneath the apparently unruffled surface of life.

Nathalie Sarautte, Tropisms, (1957), trans. Maria Jolas, New Directions, 2022.

Remote but charged with intensity, Sarautte’s short stories offer glimpses beneath the apparently unruffled surface of life. Each brief piece illuminates, but just for a moment, what Hannah Arendt described in her review of Tropisms as the ‘microcosm of the self’. As a wry, unforgiving observer of human behaviour, Sarautte shows how in the blink of an eye comedy or love can turn to cruelty or hate, as she exposes ‘the frontiers of consciousness’, hidden ‘under the commonplace, harmless appearance of every instant’.

Nathalie Sarautte, Tropisms, (1957), trans. Maria Jolas, New Directions, 2022.

Remote but charged with intensity, Sarautte’s short stories offer glimpses beneath the apparently unruffled surface of life. Each brief piece illuminates, but just for a moment, what Hannah Arendt described in her review of Tropisms as the ‘microcosm of the self’. As a wry, unforgiving observer of human behaviour, Sarautte shows how in the blink of an eye comedy or love can turn to cruelty or hate, as she exposes ‘the frontiers of consciousness’, hidden ‘under the commonplace, harmless appearance of every instant’.

Namwali Serpell

The Furrows

An elegy for the destabilising impact of traumatic loss and its effect on identity, Serpell’s view of the world is one that is ‘made up of threads of possibility, all the coulda-woulda-shoulda’s’.

Namwali Serpell, The Furrows, Hogarth, 2022.

Caught between her own fragmentary memories of her brother’s death, her mother’s assertion that he is still alive and the adult world’s mistrust of her story, as the sole witness, C experiences and re-experiences this loss, but always anew, always occurring in a different place, always only half remembered. In adult life, C encounters a man over and over again who seems familiar and who bears the same name as her brother, but each time the encounter heralds a different but always cataclysmic event. An elegy for the destabilising impact of traumatic loss and its effect on identity, Serpell’s view of the world is one that is ‘made up of threads of possibility, all the coulda-woulda shoulda’s’, where lives are caught up in the furrows, where time shifts or flattens out, but always falls back into those same ‘relentless grooves’.

Namwali Serpell, The Furrows, Hogarth, 2022.

Caught between her own fragmentary memories of her brother’s death, her mother’s assertion that he is still alive and the adult world’s mistrust of her story, as the sole witness, C experiences and re-experiences this loss, but always anew, always occurring in a different place, always only half remembered. In adult life, C encounters a man over and over again who seems familiar and who bears the same name as her brother, but each time the encounter heralds a different but always cataclysmic event. An elegy for the destabilising impact of traumatic loss and its effect on identity, Serpell’s view of the world is one that is ‘made up of threads of possibility, all the coulda-woulda shoulda’s’, where lives are caught up in the furrows, where time shifts or flattens out, but always falls back into those same ‘relentless grooves’.

Magdelena Tulli

Flaw

Concerned with notions of chance and the indifference of onlookers, Tulli positions herself as the observed and the observer, sometimes stepping into the shoes of the maid, the student, or the housewife who watches scenes from her apartment window.

Magdelena Tulli, Flaw, (2006), trans. Bill Johnson, Archipelago Press, 2007.

The scene: a square encircled by a tramline in an unknown city, in an undefined time. The characters, like the representatives of their work or class in August Sander’s photographs, we know only as the maid, the notary, the student, the housewife, the pharmacist, the soldier. All appears as usual until a putsch ruptures daily life and the square quickly fills with refugees: the orphans, the newlyweds, the pregnant woman, the anxious father. Chaos ensues and social mores are overturned, bringing the fate of the refugees into the hands of those with freshly acquired power. Concerned with notions of chance and the indifference of onlookers, Tulli positions herself as the observed and the observer, sometimes stepping into the shoes of the maid, the student, or the housewife who watches the scenes from her apartment window. Written as snapshots, each moment speaks to history and the societal distortions that sudden and violent change brings, showing us that life is uncertain with no guarantees.

Magdelena Tulli, Flaw, (2006), trans. Bill Johnson, Archipelago Press, 2007.

The scene: a square encircled by a tramline in an unknown city, in an undefined time. The characters, like the representatives of their work or class in August Sander’s photographs, we know only as the maid, the notary, the student, the housewife, the pharmacist, the soldier. All appears as usual until a putsch ruptures daily life and the square quickly fills with refugees: the orphans, the newlyweds, the pregnant woman, the anxious father. Chaos ensues and social mores are overturned, bringing the fate of the refugees into the hands of those with freshly acquired power. Concerned with notions of chance and the indifference of onlookers, Tulli positions herself as the observed and the observer, sometimes stepping into the shoes of the maid, the student, or the housewife who watches the scenes from her apartment window. Written as snapshots, each moment speaks to history and the societal distortions that sudden and violent change brings, showing us that life is uncertain with no guarantees.

Annie Ernaux

Simple Passions

‘From September last year I did nothing else but wait for a man’, Ernaux writes in this characteristically personal and honest account of an intensely lived time in her life.

Annie Ernaux, Simple Passions, (1991), trans. Tanya Leslie, Fitzcarraldo Editions,

2022.

‘From September last year I did nothing else but wait for a man’, Ernaux writes in this characteristically personal and honest account of an intensely lived time in her life. Describing her obsessive affair with a married man, she traces the course of this infatuation, dissecting her thoughts and actions which were entirely focused on desire for A. Describing the book as ‘an offering bequeathed to others’, Ernaux acknowledges that if nothing else, the experience ‘brought her closer to the world’, enabling the realisation that hers was not a unique story, but simply part of the human condition.

Annie Ernaux, Simple Passions, (1991), trans. Tanya Leslie, Fitzcarraldo Editions,

2022.

‘From September last year I did nothing else but wait for a man’, Ernaux writes in this characteristically personal and honest account of an intensely lived time in her life. Describing her obsessive affair with a married man, she traces the course of this infatuation, dissecting her thoughts and actions which were entirely focused on desire for A. Describing the book as ‘an offering bequeathed to others’, Ernaux acknowledges that if nothing else, the experience ‘brought her closer to the world’, enabling the realisation that hers was not a unique story, but simply part of the human condition.

André Gide

Strait is the Gate

Inspired by Gide’s own love for his cousin, the novel is an exploration of the self and how to balance the religious and social values of the early twentieth century with personal desires and freedom.

André Gide, Strait is the Gate, (1909), trans. Dorothy Bussy, Penguin Classics, 2001.

When a young boy, Jerome fell in love with his cousin Alissa and vowed to dedicate his life to her. Alissa, although deeply in love with Jerome, comes to believe that she must sacrifice their love for the sake of both their souls. Dedicating her life to God, she suppresses her emotions and attempts to distance herself from her cousin, realising only at the last that her sacrifice has been in vain. Shaped by their personal childhood losses, each in adulthood tenaciously maintain their ideals of love, a situation which becomes clear to Jerome only in later life as he recounts their story. Inspired by Gide’s own love for his cousin, the novel is an exploration of the self and how to balance the religious and social values of the early twentieth century with personal desires and freedom.,

André Gide, Strait is the Gate, (1909), trans. Dorothy Bussy, Penguin Classics, 2001.

When a young boy, Jerome fell in love with his cousin Alissa and vowed to dedicate his life to her. Alissa, although deeply in love with Jerome, comes to believe that she must sacrifice their love for the sake of both their souls. Dedicating her life to God, she suppresses her emotions and attempts to distance herself from her cousin, realising only at the last that her sacrifice has been in vain. Shaped by their personal childhood losses, each in adulthood tenaciously maintain their ideals of love, a situation which becomes clear to Jerome only in later life as he recounts their story. Inspired by Gide’s own love for his cousin, the novel is an exploration of the self and how to balance the religious and social values of the early twentieth century with personal desires and freedom.,

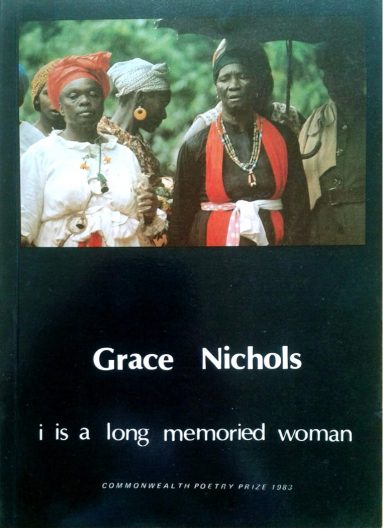

Grace Nichols

I is a Long Memoried Woman

Influenced by the rhythms and structural patterning analogous to oral storytelling, this poetry cycle gives voice to the long memoried woman who bears witness to the enslavement of her peoples in the Caribbean sugar plantations.

Grace Nichols, I is a Long Memoried Woman, (1983), Karnak House, 1999.

Influenced by the rhythms and structural patterning analogous to oral storytelling, this poetry cycle gives voice to the long memoried woman who bears witness to the enslavement of her peoples in the Caribbean sugar plantations. Expressed with the dignity of the survivor, she recalls long-lost Dahomey, her capture, and the Middle Passage. She speaks too of the years of physical and psychological violence, the double pain of childbirth endured by women forced to bring new lives into enslavement, and of the winds of change which she envisages will dismantle the system of her suffering.

Grace Nichols, I is a Long Memoried Woman, (1983), Karnak House, 1999.

Influenced by the rhythms and structural patterning analogous to oral storytelling, this poetry cycle gives voice to the long memoried woman who bears witness to the enslavement of her peoples in the Caribbean sugar plantations. Expressed with the dignity of the survivor, she recalls long-lost Dahomey, her capture, and the Middle Passage. She speaks too of the years of physical and psychological violence, the double pain of childbirth endured by women forced to bring new lives into enslavement, and of the winds of change which she envisages will dismantle the system of her suffering.